George Monbiot, in the Graun, with a lead pipe. By which I mean it is the usual bludgeoning. He has various points, many of them semi-valid, including the superior efficiency of a non-beef diet, to which I feel a great deal of sympathy. But I don't want to talk about that, I want to look at a thing he points at for his cropland doom, the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification's Global Land Outlook. I went expecting to be disappointed and they didn't disappoint me about being disappointing. You can skip the next couple of paragraphs if you don't care about that stuff but only want the yields are already declining on 20% of the world’s croplands stuff. I find some interesting discussion of vaguely similar points from a 2008 post of mine. In 2009 I looked at Could Food Shortages Bring Down Civilization? but failed to say "Betteridge".

George Monbiot, in the Graun, with a lead pipe. By which I mean it is the usual bludgeoning. He has various points, many of them semi-valid, including the superior efficiency of a non-beef diet, to which I feel a great deal of sympathy. But I don't want to talk about that, I want to look at a thing he points at for his cropland doom, the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification's Global Land Outlook. I went expecting to be disappointed and they didn't disappoint me about being disappointing. You can skip the next couple of paragraphs if you don't care about that stuff but only want the yields are already declining on 20% of the world’s croplands stuff. I find some interesting discussion of vaguely similar points from a 2008 post of mine. In 2009 I looked at Could Food Shortages Bring Down Civilization? but failed to say "Betteridge".As you'd expect, the report isn't friendly to agribiz; their solutions are about "managing" things. Bureaucrats good, never markets. And we get stuff like Small-scale farmers, the backbone of rural livelihoods and food production for millennia, are under immense strain from land degradation, insecure tenure, and a globalized food system that favors concentrated, large-scale, and highly mechanized agribusiness. No, that's not the right way to think about that kind of problem; this is more longing for the Merrie England Happy Peasant type stuff that no-one who can possibly avoid it will actually choose to live with. People abandon peasant agriculture when they can, for the obvious reasons. Their Happy Peasant culture of dancing around maypoles will be lost, just like ours has been.

Much of the early sections reads like boilerplate; things that other people have written, and they've copied, without even thinking about. Take, for instance, The widening gulf between production and consumption, and ensuing levels of food loss / waste, further accelerates the rate of land use change, land degradation and deforestation. What does that even mean? There can't be a large excess of consumption over production, the gulf can't be that way round, otherwise we'd run out of things to consume, which is physically impossible. So they must mean that production now greatly exceeds consumption. If true, that would be mad, but it would also be a cause for hope: because if you could then cut down on the waste - presumably, the "gulf" in that case comes from waste, I think even the EU has stopped just throwing food away, though even that is indeed waste - you could feed more people from the same land, which would be good. Is that what they mean? I don't know. I get the feeling they've been told to bang out a report, lots of references, at least 1" thick 2" would be good, never mind about the actual words too much.

Anyway, so much for intro, the bit I wanted was A significant proportion of managed and natural ecosystems are degrading and at further risk from climate change and biodiversity loss. From 1998 to 2013, approximately 20 per cent of the Earth’s vegetated land surface showed persistent declining trends in productivity, apparent in 20 per cent of cropland, 16 per cent of forest land, 19 per cent of grassland, and 27 per cent of rangeland. These trends are especially alarming in the face of the increased demand for land-intensive crops and livestock.

But we also learn, from the start of Chapter 4, that Over the last 20 years the extent of land area harvested has increased by 16 per cent, the area under irrigation has doubled, and agricultural production has grown nearly threefold. These two ideas aren't incompatible of course. We can be increasing productivity in some places while losing it in others. We could be grabbing good new land while throwing wrung-out old land away. Maybe.

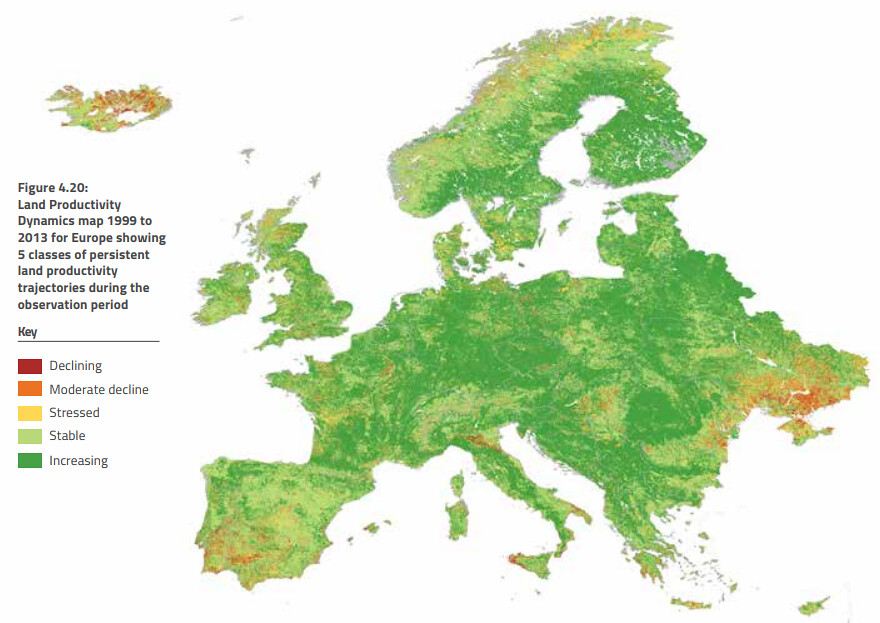

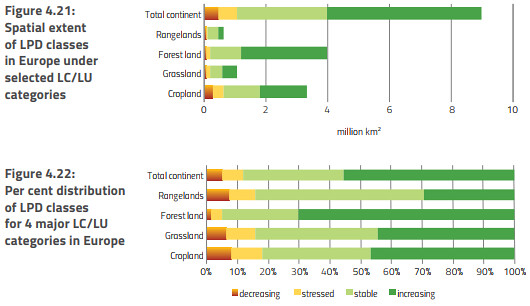

But as Chapter 4 says, Measuring the extent of land degradation is difficult, so we didn't try to do it we just nicked The World Atlas of Desertification (WAD) instead. It appears to be an EU product. For an example pic, see Europe inlined above. I've cheated; Europe is the greenest. But is that cheating? Europe is intensively inhabited and intensively farmed; why isn't it desertifying, if that's the problem we're worried about? The answer is obvious: Europe is also run by wealthy people who look after the land, in general. Perhaps that's the solution?

But as Chapter 4 says, Measuring the extent of land degradation is difficult, so we didn't try to do it we just nicked The World Atlas of Desertification (WAD) instead. It appears to be an EU product. For an example pic, see Europe inlined above. I've cheated; Europe is the greenest. But is that cheating? Europe is intensively inhabited and intensively farmed; why isn't it desertifying, if that's the problem we're worried about? The answer is obvious: Europe is also run by wealthy people who look after the land, in general. Perhaps that's the solution?The report is keen to guide your eye, and will tell you for example that Indications of decreasing productivity can be observed globally, with up to 22 million km2 affected, i.e., approximately 20 per cent of the Earth’s vegetated land surface shows persistent declining trends or stress on land productivity. But if you look at Europe, you'll see that more than 50% is deep-green, which is to say "increasing". That doesn't get a mention (they can't avoid mentioning Europe entirely of course, so they say Local farming practices often result in water and wind erosion and other degradation phenomena that, however, cannot be captured universally at the scale of analysis with the current datasets available; they know there's a problem, even if they can't see it). Even globally, the "deep green" total is bigger than the red-plus-yellow bits. That doesn't mean all is well, but it does deserve noticing; I can't think that a report that doesn't notice that is balanced.

I'd better stop before I channel any more of the spirit of Bjorn Lomborg. Global warming is bound to bring shifts to rainfall patterns that are bound to disrupt our agriculture and natural ecosystems in ways that are hard to predict in any kind of detail. I do caution against lack of caution.

Refs

* Does Eating Meat Contribute to Global Warming?

You went a little apples-oranges in paragraphs 4 and 5, ag land being a (smallish?) fraction of all vegetated land.

ReplyDeleteOCO-2 should be very informative about this trend. I don't recall if one of the initial papers relates, but if not a few more years of data should do the job.

Locally, the problem is that none of the wheat producing regions suffered drought last growing season. So the price for the soft white "noodle" wheat is so low, for the 3rd year in a row,that some of the producers are likely to go under.

ReplyDeleteYou can, of course, refer to the immensely exciting World Food Situation reports at:

ReplyDeletehttp://www.fao.org/worldfoodsituation/csdb/en/

Which do actually show production increasing over consumption, marginally over the past few years. Stocks of cereals have increased by ~200 million tonnes over the past ~5 years.

So it's unlikely that production drops are going to starve us any time soon. But's it's worth considering that we still only have 100 days of food supply for the world, so something like a big volcanic eruption, meteorite strike or even major trade disruption could mes things up very quickly. (Living in a food-importing country that seems to be on the verge of completely cutting itself off from global trade could be cause for concern).

Is anybody ever going to get around to admitting that broadly speaking, Lomborg was correct? About almost everything in TSE?

ReplyDeleteAge must be getting to Tom's memory.

ReplyDeleteI just flew back from a climate conference, we discussed finding ways to get ordinary people (not us elites) to lead humble low-carbon lifestyles, turn off the lights, turn off the heat, walk instead of drive, how to make bicycles out of bamboo (grows fast with 400 ppm C02) so I want you all to seek new says to sacrifice and reduce your carbon footprints. No more meat, only hand picked salads.

ReplyDeleteOnly then can China make the great leap forward to a panda that eat shoots and bicycles.

ReplyDelete@JB, There are multiple paths the future can follow.

ReplyDeleteOne is where we burn all the conventional and unconventional fossil fuels. Atmospheric CO2 would double about 5 times, global average temperature would rise by by 20C or so, most of the tropics to mid latitudes would be too hot for vertebrates at least seasonally, and the polar regions are subtropical in climate. Palm trees and alligators on Greenland. What would you say to a person living in such a far future world? The only good news for you is there wouldn't be many to apologize to. Oh, and no more fossil carbon fueled lifestyle.

Another is one where we switch to nuclear power, electric cars and electric heat. The world's nuclear weapons could be torn down to provide fuel for the reactors. As JMc pointed out, this path could last for the expected lifetime of the biosphere.

http://web.archive.org/web/20130105030059/http://www-formal.stanford.edu/jmc/progress/index.html

(Parts of this show age. Solar power, for example, has gotten dramatically cheaper.)

Or perhaps we could expand solar power with various energy stores enough.

Or some mix of solar and nuclear.

There are vastly more, of course.

The question I have for you is: how do we avoid the first path?

>"how do we avoid the first path?"

ReplyDeleteMany ways, perhaps easiest is do nothing and let economics change the way we generate energy. BAU is now nothing like the old BAU scenarios.

Maybe my last post isn't quite right. Economics may well convert heating and land transport to renewables well before ff are exhausted but flying might still need some incentive or sequestration. There again perhaps we will have suborbital rockets for long distance and electric planes and/or hyperloop for shorter distances. Biosphere sequestrated rocket fuel might well become possible and maybe even cheaper than extracting ff and refining them. If it becomes possible but not cheaper then some incentives may be needed.

ReplyDeleteIf the task is to do it before all ff are exhausted then there is lots of time to accomplish this. More realistically, there is a need to ensure that it happens much sooner than that and some small incentives (perhaps more aimed at air and sea transport than currently) to make it happen faster than just the economics alone seems like sensible precautionary approach.

I am posting this partly because doom-mongering is not useful, whereas inspiring people to believe that it is possible to believe we can overcome GW is much more useful. No room for complacency, still lots to be done.

I think path one is now unlikely. It seems entirely plausible that we'll stop at doubling CO2, though that's mostly feel; I haven't actually looked at any scenarios recently. It is harder to see planes being converted; but flights are ~2% of CO2; if that was all we were emitting, there wouldn't be much problem.

ReplyDeleteI think air transportation is actually closer to 5%, source faded into the mists of time...

ReplyDeleteStill small beer, really and improved engines helping as we go forward.

If George wants us to eat less beef, and take a bite out of Lyme disease, he should stop dissing frozen foods and lobby for a longer deer season.

ReplyDelete