Tom asked about "Doughnut Economics"; I'm very tempted to just reach for the W-word, but since he was also kind enough to ask for more posts, I'll post on it.

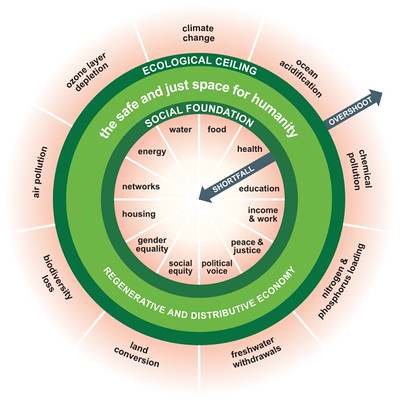

Tom asked about "Doughnut Economics"; I'm very tempted to just reach for the W-word, but since he was also kind enough to ask for more posts, I'll post on it. We need to begin by working out what this stuff is. They offer The Doughnut offers a vision of what it means for humanity to thrive in the 21st century - and Doughnut Economics explores the mindset and ways of thinking needed to get us there and the economic thinking needed. So I deduce it is a way of thinking; a way of thinking about economics. However The Doughnut's holistic scope and visual simplicity, coupled with its scientific grounding, has turned it into a convening space for big conversations about reimagining and remaking the future is really very off-putting and I feel the W-word looming. You have been warned.

The idea is to change the goal from endless GDP growth to thriving. Well, I've heard that one before, of course. So first of all her terminology is wrong: the present-day aim of GDP growth is a political, not economic goal. This indicates muddled thinking on her part, but may not be fatal. As any fule kno, Economics is the social science that studies how people interact with value; in particular, the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. Complaining that when she says econ she really means pol would be mere semantics; but the unanswered question at this point is whether a new goal, which we will choose and use econ thinking to work out how to achieve - this would require no new econ, merely pol; or whether she has some substantive criticism of existing economics, not politics, - errors in existing anaylsis, important previously-ignored components - that will force us to revise our economic analysis. That she is unable to state the question clearly isn't encouraging.

Initially, it looks very much like pol: her very first idea it to change the goal, from increasing GDP, to "the Doughnut". An immediate objection is that GDP is at least clear, whereas her alternative is vague. Another objection is that "increasing GDP" isn't many people's goal. It isn't mine, and it isn't yours. It is the sort of thing that govts tend to claim to do, because people tend to like increasing prosperity. But I think she is somewhat confusing emergent properties with goals; like those funny denialists who insist that climate models have set sensitivities. Items 2-7 are so wanky (damn! I finally said it out loud) that I can't comment without looking deeper.

But there doesn't seem to be much depth. Take, for example "peace and justice" (sadly, there's isn't a "motherhood and apple pie" element). So, I'm sure we'd all agree that Peace and Justice are excellent things, though quite likely we'd disagree on exactly what Justice means. How will DE get us there? I've no idea.

So as far as I can tell DE reduces to "(a) it would be nice if no-one were poor or sad; and (b) using more resources than we actually have isn't sustainable in the long term; and (c) I have no real idea how to get there". Is there anything new in this, other than an infographic? You can tell, I'm pretty sure, that I'm unconvinced; if missed the depth of analysis, do please point me to it. I tried the original 2012 report, which says thing things like Income: Ending income poverty for the 21 per cent of the global population who live on less than $1.25 a day would require just 0.2 per cent of global income. And this it true... or at least it was then; since global poverty has fallen in the past 9 years and global income risen, it would now require even less. But to write it in those term completely misses the point. Most dreadfully poor people are so because their govt is crap, not because of any inherent limitations.

Refs

* History in the (re)making? - JA

* 2025/07: Throw the Doughnut away.

Thanks for posting on this. I must say I agree with your objections, but don't think they are fatal to the concept. I don't completely agree with her aims, but I don't think that is fatal to the concept either.

ReplyDeleteIf we can agree that economics is a tool, a servant rather than a master, it does not seem unreasonable to specify what it will serve. Utility by any other name...

And sure, the focus on growth in GDP is equal parts a hopefulness that increasing wealth will help the poor combined with simple observation of what has happened in recent centuries, so that seems to indicate that an end to growth doesn't mean finishing growth but identifying an aim. Not End Growth Now, but rather To What End Do We Grow?

It needs a lot of work, but the basic concept resonates with this biologist.

ReplyDeleteYou may be familiar with the concept of the ecological niche, the boundary conditions within which a species can survive.

The doughnot is an attempt to define the boundary conditions for a viable and long term sustainable civilization.

The outer boundary is easy. It defines the limits of what we can do to the planet without destroying ourselves.Much of that has a rational, scientific basis.

The inner boundary is much vaguer. It attempts to define the limits of what we can do to ourselves. Since much of that depends on which moral code you practice, it is much harder to quantify.

The outer boundary is the strongest part of the doughnut concept. The inner boundary is its weakness.

Entropic man, I actually think it's the reverse--I think the inner circle is stronger, in the sense that we can identify the scope of the issues and efforts have been made to show what we need to achieve the aims.

ReplyDeleteSuppose we were to posit that the goals of the DE were laudable. If so, the question is what are the obstacles? As our host has mentioned, a key question is whether the resources to achieve them exist. I am inclined to say yes, on a time scale of two or three generations, provided that we could all take the Chinese cure - adopting zero or negative population growth policies. Nothing else has shown similar potential for increasing the average per capita gdp, and nothing is more inimical to average per capita growth than population growth. Malthus is still the most important economist.

ReplyDeleteDr. Connolley thinks nations are poor because they have "crap governments." While that is doubtless a greatly aggravating factor, I think a far more important one is rapid population growth. The global data is all but unanimous.

If we accept the feasibility, could the doughnut be achieved? The big remaining obstacle is human nature. Evolution designed us to compete against other humans for survival, and that competitive instinct is a huge obstacle. There is no doubt that something like the DE could be achieved locally in the US, but instead we see the oligarchs fighting bitterly to keep Americans from getting universal health care and affordable housing, while they indulge themselves in superyachts, space programs, and mega mansions.

One way to see it is that the DE would require sacrifices of freedom, especially the freedom of the super wealthy to indulge in endless luxury, but also the freedom of practically everybody to reproduce as much as they like.

I think that Tom and EM disagreeing which is the hard side is typical of this stuff: it is so vague that you can read or project into it whatever you want.

ReplyDelete> The outer boundary is easy

But is it? Suppose we agree for example that on CO2 we know the climate sensitivity and we know the delta-T limit is 2 oC... where does that get us? No closer to limiting emissions; and no closer to deciding - insofar as that even means anything - who is going to limit their emissions.

> Malthus

https://wmconnolley.wordpress.com/2009/01/03/why-did-malthus-assume-linear/

> the freedom of the super wealthy

See previous post. I think this constant shuffling off of problems onto the shoulders of the "super wealthy" is just evading responsibility / politics of envy.

Might want to read some of the comments on your Malthus post. Some of the comments are sane.

ReplyDeleteAll exponentials end.

If the population is small relative to available land, farming output is mostly dependent on farmers. More farmers, more food. Both can grow exponentially. Life is as good as it gets.

As the land is filled up, food output grows slower than the farm population. Life is getting hard. There is a point when Mathus's statement would be correct. Then it gets worse.

At the limit, no more food can be grown even with added population. At some point, violence or famine or disease or something solves the problem of excess people.

Technology can improve the limit somewhat, but doesn't change the problem.

All exponentials end.

Make crazy assumptions, and you can write some science fiction. For example, assume no limits to human population growth. Lack of energy? Some magic energy creation machine. Getting rid of heat? More magic machines. Lack of matter? Create what is needed out of nothing. What happens? If we don't assume infinite material strengths, or break laws of gravity or motion, you get a ball of humans exploding at the speed of light, and at the center a rapidly growing black hole. So the question to the student is: does the black hole snuff out the explosion of humans? If so, how long does it take? Show your work. Advanced work would be showing what the gravitational waves produced would look like.

All exponentials end.

Your critique of Malthus is off the mark. There are few points in human history when much available agricultural land has not been under cultivation. The advance of technology has gradually expanded the amount of such land but it is clearly a finite resource, as is the total biological productivity of the land. So is the technology to maximally exploit the available land. That is the elementary logic behind evolution and economics.

ReplyDeleteThe evidence of modern economy is even more clear cut. With negligible exceptions, every prosperous country has a low birthrate and nearly every country that has maintained a low birth rate for forty or more years has seen a rapid growth in gdp per capita.

Spend an hour or two looking at the time history of fertility vs gdp per capita on Gapminder.

I disagree. My critique - that M's fundamental assumption that food production is linear - is both historically wrong, and theoretically unfounded: he pulled it out of a hat. My contrary idea - that food production would scale with the number of people - has a better theoretical foundation and is historically more accurate. Why people keep insisting he was right remains a mystery to me.

ReplyDelete> every prosperous country has a low birthrate and nearly every country that has maintained a low birth rate

How are you determining causality?

How are you determining causality?

ReplyDelete"that food production would scale with the number of people"

Perhaps the number of people is determined by food production would be more accurate over history.

Wow. Seems like a number of non-facts are here presented as a given.

ReplyDeleteTFP in agriculture has risen steadily since Borlaug. Agricultural production has increased at 1.5% per annum over the past 50 (?) years, while the amount of land under the plow has stayed the same. As live births are increasing at 1.1% annually, Malthus seems to be losing at the moment.

If you can tease out the primary factor behind declining birth rates from the obvious candidates, I think Stockholm is on the other line waiting to speak to you. Is it female education, improved contraception, rising incomes, lower maternal and infant mortality rates, stable societies...?

Most of Eastern Europe has experienced dramatic declines in birth rates without a corresponding rise in prosperity. As has Japan.

@WC - Linear vs. exponential is a red herring. The point is a limited resource vs. unlimited growth potential. Krugman said that Malthus was right about every era except the modern one. That's not quite right. There have been several periods where food production grew rapidly due to technological or other factors, with the modern era being the most dramatic except for the original development of agriculture. All such eras end, usually rather soon, as population quickly catches up with technology. The modern era has lasted a couple of centuries, at best, with a big contribution from the dramatically declining birth rates in the developed world.

ReplyDelete@Tom - "Malthus seems to be losing at the moment..."

ReplyDeleteExactly backwards. Malthus said limiting reproduction was the only path to eliminating starvation. That is exactly what has happened in the wealthy world, and what has failed to happen in impoverished countries.

Yes, we have had a (yet another) technological revolution in agriculture, and it has brought many decades of rapidly increasing prosperity, a microsecond in human history - except in countries where population has continued to grow rapidly.

Your comments about Japan and Eastern Europe are flat wrong. Japan was the one of the first countries to see a rapid reduction in birth rate and to reap the resulting leap in prosperity (800 % plus in real gdp). Look also at Greece, Latvia, Bulgaria, Belarus and Georgia - all have seen huge increases in real, inflation adjusted gdp.

An ideal way to see these results is Gapminder's graphical tool which allows one to, for example, plot total fertility vs gpd per capita vs. time.

@WC & Tom - Note that low birth rates depend heavily on contraception and that they facilitate female education, female employment, better child care and more resources per child.

ReplyDeleteSigh... Japan had a birth rate of 2.0 as recently as the 70s. Their economy has been stagnant since 1991, when the largest population cohort in their history turned 21.

ReplyDeleteYour singling out of the poor countries of Europe is a bit misleading, isn't it? France, Italy and Germany got rich before their birth rate cratered.

Parents in richer countries don't have to have as many children to insure continuing their genetic survival, as child mortality drops. Nor do they benefit from having uneducated free labor, as they've moved off the farm.

In richer countries, children require more of an investment in health and education, which parents willingly provide. Both factors push for a lower birth rate.

@ Sigh

ReplyDeleteTry to stay close to your fainting couch, since I have a few more facts. Per capita gdp in Japan has grown by 30% since 1990, not great but a lot better than high birth rate Niger, which only managed 10% - from a base of 886 $/yr. China first got its fertility rate below 2.5 and has since increased per capita gdp by 1147%. France reached that milestone in 1910 and has since seen its real gdp per capita increase by 828%. Italy first reached it in 1945 and has seen 1100% growth.

Lets look at Japan's growth one more time. Japan broke 2.5 fertility in 1955, and has since totaled 920% gdp growth.

If you look closely at the at the growth-fertility curve, it is something of a one time bonus. Eventually the fraction of less productive older persons slows your growth, but if your nation has gotten 8-11 times richer in the meantime, it is much better prepared to deal with that problem.

China, by the way, is the clearest case. It did not decrease fertility because it got richer, it was desperately poor when a dictatorial government enacted the one child policy. Since then, per capita gdp has grown by 3200%.

@ Tom, Note that although the once child policy started about 20 years earlier, it did not reach the 2.5 fertility point until 1980, but had already gathered significant rewards from by decreasing fertility.

ReplyDeleteWhy would you highlight a fertility rate of 2.5, a rate that signals robust growth in the population?

ReplyDelete2.5 is not rapid population growth. 2.1 is replacement in nations with modern low child mortality. No country was as low as 2.5 in 1900 and only France was narrowly below 3.0, and most were still above 5.0 in 1960. Hapless Niger is still at 7.0.

ReplyDeleteI didn't so much pick 2.5 as observe where rapid economic growth seemed to cut in.

Again, I recommend trying it yourself. Gapminder is only a click away: https://www.gapminder.org/tools/#$state$time$value=1961;&marker$axis_y$which=children_per_woman_total_fertility&domainMin:null&domainMax:null&zoomedMin:null&zoomedMax:null&spaceRef:null;;;&chart-type=bubbles

CIP, I've been using Gapminder for more than a decade. I see no evidence to counter my opinion that economic growth enables smaller families rather than being a result of it. As I said above, improved economic opportunity means families don't need a horde of children as unpaid labor, don't need to have extra babies based on high child mortality and realize quickly that children in a high growth environment require significant investment.

ReplyDeleteI also don't think you realize how big a difference a 2.5 TFR is compared to 2.1.

In my world, cause usually precedes effect. You seem to have the opposite opinion.

ReplyDeleteA fertility rate of 2.5, in an advanced country, translates to a population growth rate of 20% per generation - about 1% per year. A fertility rate of 5.0, like most countries before 1960, translates to about 170% growth per generation. That looks like a big difference to me. In say India, where 110 males are born for every 100 females, 2.5% is significantly translates to significantly less growth.

CIP, not really sure what you mean by cause preceding effect. Population dynamics seem to be a circular phenomenon with changes having impacts. It would be just as easy to write either equation--smaller families increase wealth, increased wealth causes lower family sizes. Both would be, well wrong might be too strong a word--inadequate explanations of the phenomenon. It may be a self-reinforcing feedback loop and you and I are trying to assign responsibility to either the chicken or the egg while completely ignoring the rooster in the room.

ReplyDeleteI do think both history and academic studies side with my interpretation, but that could be overly facile.

I think a couple of examples speak loudly. Consider Saudi Arabia and China. In Saudi, an explosion of wealth had no effect on fertility until it started collapsing. At that point fertility plummeted until per capita gdp stabilized. China remained desperately poor until the one child policy. After that, the economy leaped ahead. These are some what extreme cases but they are not isolated.

ReplyDeleteOn the other hand, your model is far more tenable for the wealthy states of the West - a fact that I think has caused scholars to give it undue weight.

The most dramatic social change of the last two centuries has been the education of women and their entry into the work force and body politic. It was extremely had for that to happen when the were raising half a dozen or more children.

Perhaps then it would be fairer (if harder to measure) to say that awareness of economic opportunity (and relocation to urban areas) put downward pressure on TFR.

ReplyDeleteBut I don't think either is as important as the Pill.