Following

in CIPs footsteps, only nine years behind the times. There's no hurry. I'm interested from the perspective of foundations-of-morality-and-law, to put my biases up front; and so will ignore sections orthogonal to that. I want to argue for an abstract morality; I can cope with what I think is JH's evolution-influenced morality if I can fit it into a paradigm that only certain moralities are possible; that others fail to produce stable societies. This is a long and I think worthwhile book, even if I didn't agree with all of it. This review doesn't really do it justice; it is more about my own preoccupations. Now read on.

Chapter one: where does morality come from?

Conclusions:

* The moral domain varies by culture. It is unusually narrow in Western, educated, and individualistic cultures. Sociocentric cultures broaden the moral domain to encompass and regulate more aspects of life.

* People sometimes have gut feelings-particularly about disgust and disrespect-that can drive their reasoning. Moral reasoning is sometimes a post hoc fabrication.

* Morality can't be entirely self-constructed by children based on their growing understanding of harm. Cultural learning or guidance must play a larger role than rationalist theories had given it.

If morality doesn't come primarily from reasoning, then that leaves some combination of innateness and social learning as the most likely candidates. In the rest of this book I'll try to explain how morality can be innate (as a set of evolved intuitions) and learned (as children learn to apply those intuitions within a particular culture). We're born to be righteous, but we have to learn what, exactly, people like us should be righteous about.

I'm happy with most of that, and if I keep agreeing with him this may be a short review (in particular I think I can make it not contradict

The Enlightenment Project's "sought to found [morality] on the rational choice of its subjects rather than on tradition or local prescription")

5. That Western morality is "narrower" is good; refer to Popper / Hayek. The third point isn't quite self-contained: he is referring to a previous theory that morality comes mostly from harm-is-wrong. He finds himself forced to abandon this theory: most obviously in sociocentric (non-individualistic) cultures, but to a lesser extent in the West, non-harm taboo-violations are viewed as immoral. However, the interpretation is the charm...

Consider one of his taboo-violation-as-immorality stories: a family accidentally runs over their pet dog and kills it. No-one sees. They take the dog inside and eat it. No-one knows. Is this immoral? Essentially everyone squirms at this and (apparently) when he gave this as a test, people kept making up spurious reasons why people might have been harmed. I think it is kinda1 immoral4, and the harm is that they are harming themselves or "their soul". they are knowingly violating a strong taboo in their society; they know they cannot tell anyone else; this stress will damage them2, and having people with "damaged souls" is bad for society, i.e. it harms others (I don't think you're obliged to agree with me here. But I hope you're surprised like me that JH failed to think of it). So we can end up with a principle-of-morality as not-violating-taboo, without having to care when thinking in the abstract just what the taboo is.

Chapters two, three and four are not relevant for my purposes (but I read them).

Somewhere along the line, JH notes that while people's reason is poor at picking up errors in their own instinctive judgements, it can be good at picking up others'. This feels true. What he doesn't bring out of that is that slow conversation - blogs perhaps - can be a better way of talking than F2F discussion.

That concludes part I.

Chapter 5: beyond WEIRD morality

WEIRD philosophers since Kant and Mill have mostly generated moral systems that are individualistic, rule-based, and universalist. That's the morality you need to govern a society of autonomous individuals. But when holistic thinkers in a non-WEIRD culture write about morality, we get something more like the Analects of Confucius, a collection of aphorisms and anecdotes that can't be reduced to a single rule. Confucius talks about a variety of relationship-specific duties and virtues (such as filial piety and the proper treatment of one's subordinates). But this is confusing morality-schemas with actual concrete codes-of-morality.

Kant isn't producing a specific code; Confucius is; or even more, producing a guide to a code; which would naturally be illustrated by examples.

Towards the end of the chapter he comes close to saying he can understand how the Repubs might not be evil; but you can tell he really still believes in the Dems.

Chapter six (Taste Buds) is probably introducing an important-to-him idea, but is thin. He considers care/harm, fairness/cheating, loyalty/betrayal, authority/subversion, sanctity/degradation but really all the first four fit under harm.

Chapter 7: the Moral Foundations of Politics

Kinda goes though the same pairs as chapter 6, but slightly differently. But... well, example: We are the descendants of successful tribalists, not their more individualistic cousins. I think this is true, but irrelevant to morality. It can explain instincts and behaviour, but not morals. Or one of the most important insights into the origins of morality is that "selfish" genes can give rise to generous creatures, as long as those creatures are selective in their generosity. Altruism toward kin is not a puzzle at all. Altruism toward non-kin... Robert Trivers published his theory of reciprocal altruism... evolution could create altruists in a species where individuals could remember their prior interactions with other individuals and then limit their current niceness to those who were likely to repay the favor. This too is true, but is again mixing instinct and morality. Altruism is not a moral requirement: you are not required to behave altruistically. If someone behaves A to you, you are semi-required to reciprocate, but that's different. Discusses disgust/sanctity in the context of food-gathering by omnivores, which again may explain our visceral disgust, but again not morality... and has effectively been re-purposed into taboo enforcement3.

Is some of this stuff backwards? He uses the idea of "the sanctity of the natural environment", as indeed do many others, but this is inappropriate: rather, it is retrofitting the word "sanctity" on, in order to trigger the desired emotions. Now I get to the end, I discover that what he was trying to tell us is how/why these pairs evolved.

Chapter 8: the conservative Advantage

This seems close to the core of the book, judged by the title: it applies his theories to explain... well, why some people are Repubs. Betraying the biases of his audience, perhaps, he doesn't seem to need to feel any urge to explain why some people are Dems.

But, to his credit, he is pushing against the all-too-common narrative of "explaining away" Repubs as damaged-in-childhood or somesuch.

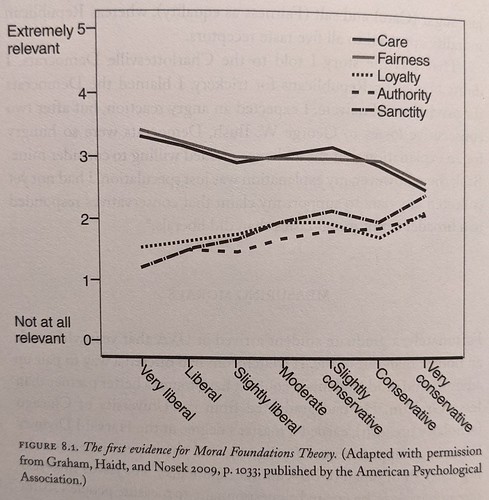

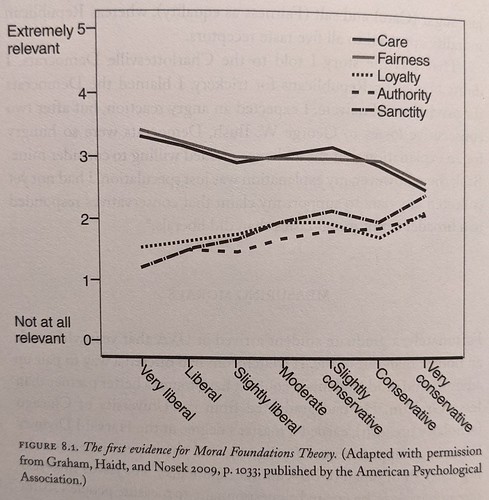

Instead (see pic) he finds that Libs weigh Care+Fairness highly, nearly to the exclusion of all else; whereas Cons weight them all about equally. He doesn't make the obvious point that one could assert that weight-all-equally seems closer to the default; so that Libs are the ones who need explaining.

After a bit he realises that Cons also care about fairness, but in a different way: fairness of opportunity rather than outcome; but that the questions he had used to characterise fairness were more about outcome. So the throws in a liberty/oppression axis too.

That concludes part II.

Chapter 9: Why are We so Groupish?

Altruism, but possibly only or perhaps more strongly in groups. Group selection: a thing or not? But (p 199) his key is that "groupishness" is one of the "magic ingredients" for civilisational success. If that's right, then whether it is produced by evolution or conscious thought doesn't matter: it is, in his telling, a prerequisite for civ. Some of this requires faster evolution, and he proposes that there's been more genetic pressure in the Holocene. Indiv vs Group morality: a real thing? See-also

Shikasta.

Chapter 10: the Hive Switch

My hypothesis in this chapter is that human beings are conditional hive creatures. We have the ability (under special conditions) to transcend self-interest and lose ourselves (temporarily and ecstatically) in something larger than ourselves... can only be explained "by a theory of between-group selection,"... an adaptation for making groups more cohesive, and therefore more successful in competition with other groups. I think I don't mind giving him that, but don't think I have to greatly care. I'm more dubious about If the hive hypothesis is true, then it has enormous implications for how we should design organizations, study religion, and search for meaning and joy in our lives. I can give him "study religion". But as a way of searching for meaning it seems desperately fake, even if it makes some people happy. Ditto, for organisations. He uses it to explain why marching makes good armies. I can't see it making good software engineers.

The yearning to serve something larger than the self has been the basis of so many modern political movements. Here's another brilliantly Durkheimian appeal:

[Our movement rejects the view of man] as an individual, standing by himself, self-centered, subject to natural law, which instinctively urges him toward a life of selfish momentary pleasure; it sees not only the individual but the nation and the country; individuals and generations bound together by a moral law, with common traditions and a mission which, suppressing the instinct for life closed in a brief circle of pleasure, builds up a higher life, founded on duty, a life free from the limitations of time and space, in which the individual, by self-sacrifice, the renunciation of self-interest... can achieve that purely spiritual existence in which his value as a man consists.

Inspiring stuff, until you learn that it's from The Doctrine of Fascism, by Benito Mussolini. And so we discover there is good and bad hivishness. My interpretation is that if your life is empty of meaning, you can get some fake meaning out of hivishness, but it's fake. Because life has no extrinsic meaning. Anyway, whilst this is relevant to politics etc its straying some distance from morality.

Chapter 11: Religion is a Team Sport

What is it good for? In other words the very ritual practices that the New Atheists dismiss as costly, inefficient, and irrational turn out to be a solution to one of the hardest problems humans face: cooperation without kinship. Again, I have no problem giving him that. But not Societies that forgo the exoskeleton of religion should reflect care fully on what will happen to them over several generations. We don't really know, because the first atheistic societies have only emerged in Europe in the last few decades. They are the least efficient societies ever known at turning resources (of which they have a lot) into off spring (of which they have few).

However we do (at last) get his "defn" of morality: Moral systems are interlocking sets of values, virtues, norms, practices, identities, institutions, technologies, and evolved psychological mechanisms that work together to suppress or regulate self-interest and make cooperative societies possible. Unfortunately he is then obliged to add: My definition of morality was designed to be a descriptive definition; it cannot stand alone as a normative definition. (As a normative definition, it would give high marks to fascist and communist societies as well as to cults, so long as they achieved high levels of cooperation by creating a shared moral order.) But I think my definition works well as an adjunct to other normative theories. So yes it may describe morality but it also describes not-morality. Whereas The field of normative ethics is concerned with figuring out which actions are truly right or wrong.

This is all getting a bit confused, and we end up with I don't know what the best normative ethical theory is for individuals in their private lives. But when we talk about making laws and implementing public policies in Western democracies that contain some degree of ethnic and moral diversity, then I think there is no compelling alternative to utilitarianism. I think he's wrong in this conclusion - and it isn't clear how he deduces it from what goes before - and I think Popper agrees. Utilitarianism is broken.

Chapter 12: Can't We All Disagree More Constructively?

Dems have a harder time understanding Repubs than vice versa. Social capital; moral capital, the fundamental blind spot of the left; I rather agree with that. Both liberals and conservatives are partly wrong and partly right. The wonders of markets and spontaneous order; the healthcare / supermarket analogy. Liberals preferring intelligent design. But, alas, he has no answer to the question from which his chapter takes its name.

Conclusions

(These are mine. JH has a conclusions chapter, but its really just recapitulation) So, in the end, I think the answer to "why good people are divided" is simply that morals, law and politics are under-determined by the defensible theoretical foundations. And thus, different people / groups build conflicting superstructures; and fail to realise that the bits they disagree about are the optional bits.

Hayek, characteristically hard-to-read,

wrote:

It is a sign of the immaturity of our minds that we have not yet outgrown these primitive concepts and still demand from an impersonal process which brings about a greater satisfaction of human desires than any deliberate human organization could achieve, that it conform to the moral precepts men have evolved for the guidance of their individual actions. This is the antidote to Haidt: where we should be going.

Postscript

I feel moved to add a postscript (quote from from Hayek,

via CH):

His [Mandeville’s] main contention became simply that in the complex order of society the results of men’s actions were very different from what they had intended, and that the individuals, in pursuing their own ends, whether selfish or altruistic, produced useful results for others which they did not anticipate or perhaps even know; and, finally, that the whole order of society, and even all that we call culture, was the result of individual strivings which had no such end in view, but which were channeled to serve such ends by institutions, practices, and rules which also had never been deliberately invented but had grown up by the survival of what proved successful. The reason I do this is to remind me... there may (or may not) need to be a certain substratum (social / moral capital) to allow society to function at all; but one should remember the virtues of individuals acting on top of that.

Notes

1. At this point, I'm not committing myself to yes-or-no. I'd rather say it is clearly gray.

2. And now I think of it, this is exactly what the "magicians" in

Stations of the Tide do: deliberately violate taboos, in order to train themselves to... evil; hardness of will.

3. And JH doesn't know why or how: As with the Authority foundation, Sanctity seems to be off to a poor start as a foundation of morality. Isn't it just a primitive response to pathogens? And doesn't this response lead to prejudice and discrimination? Now that we have antibiotics, we should reject this foundation entirely, right? Not so fast. The Sanctity foundation makes it easy for us to regard some things as "untouchable," both in a bad way (because some thing is so dirty or polluted we want to stay away) and in a good way (because something is so hallowed, so sacred, that we want to protect it from desecration). If we had no sense of disgust, I believe we would also have no sense of the sacred. And if you think, as I do, that one of the greatest unsolved mysteries is how people ever came together to form large cooperative societies, then you might take a special interest in the psychology of sacredness. Why do people so readily treat objects (flags, crosses), places (Mecca, a battlefield related to the birth of your nation), people (saints, heroes), and principles (liberty, fraternity, equality) as though they were of infinite value? Whatever its origins, the psychology of sacredness helps bind individuals into moral communities. When someone in a moral community desecrates one of the sacred pillars supporting the community, the reaction is sure to be swift, emotional, collective, and punitive (emphasis mine).

4. I find support for roughly my viewpoint (or perhaps more accurately: my viewpoint is roughly in agreement with H) in

Hazlitt's

The Foundations of Morality:

And this principle has the widest bearings. We do and should obey rules, in law, manners and morals, simply because they are the established rules. This is their utility. We cooperate better in helping to achieve each other's ends by acting on rules on which others can count. We cooperate by being able to rely on each other, by being able to anticipate with confidence what the other fellow is going to do. And we can have this essential mutual confidence and reliance only if both of us act in accord ance with the established rule and each knows that the other is going to act in accordance with the established rule. Still better, he is somewhat echoing Hayek. So: that people are able to violate taboos is evidence that they will not follow the generally established rules. And it is no good saying "oh but it was a one-off".

5. Actually for societies-in-practice I have to back off that "rational founded", and retreat to "underdetermined". See-also the link to the ACX review below. And then I should emphasise more his "Western morality is narrower" as a virtue. So the project to found morality rationally is good, taken together with that leading to less things being covered by the moral domain, and that being a sign of, in the absence of a better word, a more advanced civilisation.

Refs

*

Reviewed at ACX, 2022: says some things worth reading; but seems all rather off the point to my mind; rather focussed on (a) socialism (why?) and (b) Trump as a counter-example; I think incorrectly. The point missed is not that Haidt can

explain people's political opinions; rather that we should expect people to have different opinions, because morality is underdetermined by fundamentals and people fill the gap with local/group norms.

* Political self-government depends on moral self-government -

via CH.