AKA "

Some ideas are so stupid that only intellectuals believe them"

1. Although in this case I mean philosophers, not intellectuals. And I don't really mean believe - I mean take seriously, give - ha - time to. There are so many totally dumb ideas that nonetheless get ritually considered, because they are part of the canon. And somehow philosophy has no way to purge itself of this stuff. And so we come to

The Unreality of Time by the aforementioned McT. My link is to wiki, which offers us

McTaggart argues that time is unreal because our descriptions of time are either contradictory, circular, or insufficient. That seems dumb to me: just because we've failed to decribe a thing doesn't make it unreal. I should warn you that I have very little patience with this drivel so haven't exactly studied in close detail; so this is just a rant. If you happen to be a McT scholar who believes this stuff is worth anything, do comment.

Wiki is, in my opinion, often somewhat dodgy on philosophy, due to WP:OWN problems, so let's turn to SEP instead. That offers us McTaggart was also a dedicated interpreter and champion of Hegel, which lowers him in my opinion, since I take my opinions on H from Popper. It also offers us McTaggart is most famous for arguing that time is unreal. He was attracted to this conclusion early in his career, perhaps as a result of smoking too much weed1, which seems fair. If I follow SEP, then McT's argument begins "Time is real only if real change occurs". It isn't clear what this means. If you use as a model a 4-d space-time Newtonian universe, then in a sense nothing changes; or if you move along the time axis, then errm, things do change. Nothing makes clear which viewpoint he has in mind, if he has anything so clear anywhere. It doesn't get ny better than that, so I'll spare you any further analysis of the A-series and similar.

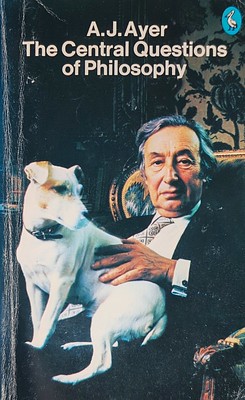

And lastly, consider the case of A J Ayer, who is I think not a clown, even if the cover photo he presumably chose for his The Central Questions of Philosophy makes him look like a bit of a ponce, although that page does say Beginning with his sceptical dismissal of metaphysics, particularly the British neo-Hegelian thinkers... I give you his text, below, if you can be bothered to try to read it. My wife, when she started reading it, didn't get far before bursting into laughter.

That wasn't very satisfying, was it? Well, not for you. But I enjoyed writing it.

Update: more Ayer

We're on page 32; I'm wading my way through a sea of blood, like MacBeth. He is trying to say something about reality and maths, I think, and asserts that even simple things like length are complicated, because no actual measurement can have an irrational number as its result. But this is wrong. We are used to measuring in units, and integer divisors of those units, but it isn't necessary. We could use irrational divisors of our base unit: I could declare that a given length has been measured as 1 + sqrt(2), just as easily as saying it is 2.141, to that degree of precision. For weights, he regards the possible (true) values (of weighing a given object) as rational but infinite in number (and therefore there are more values than our apparatus can distinguish). But I don't see why this is true; he knows atomic theory; the possible values are finite, even if there are very many of them; nor is it clear why they should be rational.

Another thought: evaluating text

Philosophy is words. Unfortunately, it is hard to evaluate words. Unlike, say, software, which can be evaulated by being compiled, run, tested. Or physics, which can be compared to reality. It is depressingly easy to write piles of words with no meaning; or with ambiguous and therefore useless meaning; and people are good at "rescuing" text from their favourites rather than admit that it is all wank; per Ayer on McT.

Notes

1. I have subtly altered this quotation, see if you can spot my change.

Text from Ayer

Starting at page 15: Let us begin then with the argument by which McTaggart sought to demonstrate the unreality of time. McTaggart begins by remarking that we have two ways of ordering events in time. We speak of them as being past, present or future, and we also speak of them as being before or after or simultaneous with one another. He then argues that the first of these ways of speaking cannot be reduced to the second, since the second makes no provision for the passage of time. Whereas the same event is successively future, present and past, there is no change in its temporal relations to other events. The fact that one particular event precedes another is equally a fact at any time. So to do justice to our concept of time, we have to make use of the predicates of past, present and future. But then, McTaggart argues, we fall into contradiction. For these predicates are mutually incompatible, and yet they are all supposed to be true of every event.

The obvious answer to this is that there would be a contradiction if we supposed these predicates to be simultaneously true of the same event, but that this is not what we suppose at all; we apply them to the same event successively. McTaggart considers this answer, and his rejoinder to it is that it escapes the contradiction only at the cost of launching us on a vicious infinite regress. We say of a contemporary event that it is present, has been future, and will be past; and what this means, according to McTaggart is that the event is present at a present moment, future at a past moment, and past at a future moment. But then the same difficulty arises with respect to these moments. Each of them is assigned the incompatible predicates of being past, present and future. We can again try to escape the contradiction by saying of the moments in their turn that they are present at present moments, past at present and future moments, and future at past and present moments, but then the same difficulty arises with respect to this second series of moments, and so ad infinitum.

The argument still seems sophistic, but it does pose a problem. So far as I can see, there are only two ways of meeting it. The one which I favour is to deny the contention that the predicates of being past, present and future cannot be reduced to the predicates of temporal order. If we take this course, we shall have to maintain that what is meant by saying of an event that it is past, present or future is just that it is earlier than, simultaneous with, or later than some arbitrarily chosen event which is contemporaneous with the speaker's utterance. On this view, the passage of time simply consists in the fact, which is itself non-temporal, that events are ordered in a series by the earlier-than relation. The passage of an event from future to present to past merely represents a difference in the temporal point of view from which it is described. This analysis has the effect of assimilating time to space, and it is, indeed, for this reason that some philosophers object to it. They feel that the river of time has somehow been turned into a stagnant pond.

The other course is to maintain that being present is not a descriptive property of an event, assigning it to a moment which itself can be described as present, past or future, but the demon strative property of occurring now. Once this is established, the past and future can safely be defined by their relation to the present. The regress is avoided by the fact that 'now' is tied to an actual context. We are not required to say when now is: our use of the word shows it. The disadvantage of this course, as opposed to the previous one, is that it introduces an irreducible element of subjec tivity into our picture of the world. It entails that an observer outside the time series, if such a thing were possible, would not be able to give a complete account of temporal facts. To do so, on this view, one has to put oneself into the picture, as an observer undergoing the passage of time.

We see, then, that while McTaggart did not prove time to be unreal, in the sense of showing all our temporal judgements to be false, his argument does... and he then proceeds to make some rather feeble excuses for why he bothered with this stuff.

Refs

* Human society is basically a phenomenon of more or less stable beliefs and patterns of conduct. The principle of [classical] liberalism is that these are not fixed once and for all – historically through prescription by some supernatural (or charismatic) authority – but are always subject to question, discussion, and alteration by agreement. Free society thus stands for progress, and also allows for and approves of much variety in both belief and conduct. From page 125 of the original 1960 Harvard University Press edition of Frank Knight’s collection of lectures, delivered in 1958 at the University of Virginia, titled Intelligence and Democratic Action, via CH.

* Hegel does maths.

Notes

1. See-also Cicero, quoted by Smith.

Possibly also: The hut on chicken's legs.

Possibly also: The hut on chicken's legs.